Academic

As a Smithsonian Research Associate I pursue 3 main themes: The life and death of societies in humans and other species; ant sociality; and the architecture of rainforest canopies, which harbor most of the earth’s biodiversity.

I have served as Associate Curator (in charge of the world's largest ant collection) and Research Associate at Museum of Comparative Zoology, Harvard University (1987-1997), Associate Curator at the Essig Museum at University of California at Berkeley (2001-2007), Visiting Scholar at the Museum of Vertebrate Zoology, also at Berkeley (1998-2006), Research Scholar at the National Evolutionary Synthesis Center, Duke (2015), and Visiting Scholar with the Department of Human Evolutionary Biology, Harvard University (1997-2000 and 2014-2020).

My undergraduate degree is from Beloit College, where I published five scientific papers and earned high honors and a Phi Beta Kappa. In graduate school at Harvard I held a National Science Foundation Fellowship. For my doctorate I carried out field research on ants for eighteen months in countries from Sri Lanka and Nepal to Hong Kong, the Philippines and New Guinea.

The Complexity Podcast put out by the Santa Fe Institute ranges widely over my interests here.

The Nature of Societies

"The rise and fall of societies has traditionally been subject matter for history and sociology, but with The Human Swarm, the author establishes the human society as a legitimate object of study for evolutionary biologists…The author’s analysis of historical examples of the rise and fall of societies through conquest and ethnic tensions between overlapping identities, or how social identity has become more complex as societies have grown in size, are masterful…The Human Swarm is a remarkable intellectual achievement of sustained intensity, to be commended for navigating an important yet difficult area in between biology, psychology, sociology, economics, history, and philosophy."

After publishing “Supercolonies of billions in an invasive ant: What is a society?” in Behavioral Ecology (see the discussion of ants, below), I expanded my interests beyond ant societies to led a session on social evolution at the 2012 conference of the Human Behavior & Evolution Society in Albuquerque. The following year my review “Human Identity & the Evolution of Societies” came out in the journal Human Nature. That article became the foundation of The Human Swarm: How Societies Arise, Thrive, and Fall, a 2019 book written as a visiting scholar at the Department of Human Evolutionary Biology at Harvard and required correspondence with nearly 500 scholars.

I am pleased that the psychology, anthropology, and sociology research communities have taken my conclusions seriously. Indeed, the leading sociology journal, Theory & Society, has published a interview of my ideas, and largest social psychology organization, the Society for Personality and Social Psychology, has put one online. The leading psychologist Marilynn Brewer described my book as "certainly the most comprehensive and compelling understanding of depersonalized societies [i.e., those allowing for strangers] that has ever been attempted," while Harvard psychologist Mahzarin Banaji wrote that "There is no other book I’ve read recently that made my neurons pop at the rate this book did.” A precís of my work is published in the Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society.

I spent much of 2024 writing a review for Behavioral & Brain Sciences, "What is a Society? Building an interdisciplinary perspective and why that's important," which was published in 2025 alongside commentaries on my ideas by leading sociologists, psychologists, political scientists, philosophers, anthropologists, archaeologists, and biologists.

Moffett, M.W. 2025. What is a Society? Building an interdisciplinary perspective and why that's important. Behavioral & Brain Sciences 1-64 PDF

Moffett, M.W. 2025. A society as a clearly membered, enduring, territory-holding group. Behavioral & Brain Sciences 54-64 PDF

McCaffrey, K. & M.W. Moffett 2025. Interview with Mark Moffett. Theory & Society PDF

Moffett, M.W. 2020. Societies, identity, and belonging. Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society 164:1-9. PDF

Moffett, M.W. 2020. Respecting nature, respecting people: A naturalist model for reducing speciesism, racism, and bigotry. Skeptics 25:48-52. PDF

Moffett, M.W. 2020. Why a universal society is unattainable: Our minds evolved in an Us-vs-Them universe of our own making. Nautilus WEB

Moffett, M.W. 2020. How societies survive. Psychology Today. 2-part interview. WEB

Moffett, M.W. 2020. Divided we stand. Project Syndicate WEB

Moffett, M.W. 2020. National borders are not going away. Quillette WEB

Moffett, M.W. 2019. How freedom divides: An expert on animal societies on what sets human societies apart. Nautilus WEB

THE LIFE AND DEATH OF SOCIETIES

My three years of effort with Templeton Foundation funding culminated in a multidisciplinary work group that I put together, kindly hosted by Yarrow Dunham the Department of Psychology at Yale in May 2025, our goal being to consider how to conceive of societies as clearly bounded units capable of lasting through the generations and controlling a territory, with the ultimate aim of describing societies throughout the human past and in those species for which comparisons to humans might be instructive. Our two women members ended up with conflicts so unfortunately we ended up being a bunch of old bearded white guys—see the picture—namely,

Kevin McCaffree, sociologist and editor of a leading journal in that field, Theory & Society;Roy Baumeister, one of the most cited social psychologists and author of many books;Francesco d'Errico, the Italian archaeologist studying the first humans to arrive in Europe;me;Peter Turchin, historian gathering massive data to look at patterns across human history;Timothy Earle, anthropologist examining the transformation of human societies over time;Yarrow Dunham, the leading cognitive scientist expert on how humans form groups.

Canopy Biology

Before my research on societies, my interest in the biology of forest canopies took me to many countries, including on expeditions of the French canopy raft, Opération Canopée.

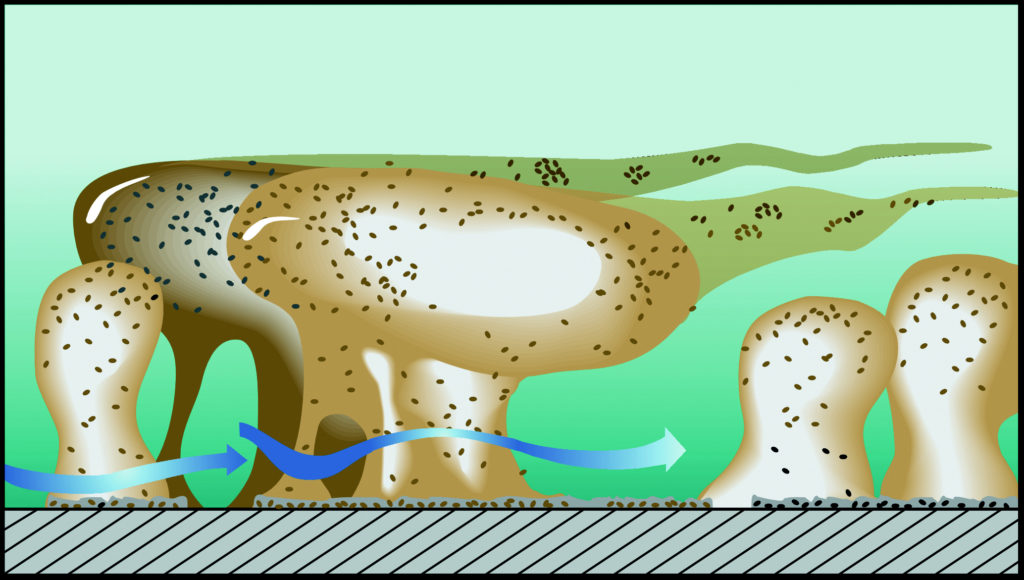

I am especially interested comparing the physical structure of ecosystems such as forests, coral reefs, grasslands, kelp forests, and biofilms (see illustration below). All these systems develop complex architectures that extract nutrients from a fluid matrix (air or water) and transfer them through food chains. Two of my reviews have been considered essential reading in the field.

I addressed these ideas early on at two critical conferences. University of California-Berkeley scientist Mimi Koehl and I organized the first dialogue between experts on marine and terrestrial canopies for the Western Society of Naturalists; I also led a session on vertebrates in the canopy at the 18th Congress of the International Primatological Society in Adelaide. My 2020 lecture for the Santa Fe Institute on comparative canopy biology and the structure of ecosystems is here.

Moffett, M.W. 2013. Comparative canopy biology and the structure of ecosystems. Pages 13-54, in M. Lowman, S. Devy, and T. Ganesh, editors. Treetops at Risk: Challenges of Global Canopy Ecology & Conservation. New York: Springer. PDF

Moffett, M.W. 2002. The highs and lows of tropical forest canopies. Journal of Biogeography 29:1264-1265. I consider the confusion stemming from the varied ways scientists talk about canopies and canopy biology. PDF

Moffett, M.W. 2000. What's "up"? A critical look at basic terms of canopy biology. Biotropica 32:569-596. This invited paper deals with conceptual ramifications of the vocabularies of ecologists, botanists, zoologists, anthropologists, aerodynamics experts, and others. PDF

The thin film that builds up on your teeth or on dirty dishes actually resembles a forest of bacteria that come together to form little “trees” called microcolonies. Such similarities across ecosystems suggest commonalities in physical organization and the accommodation of the diversity of life.

The Social Behavior of Ants

"Where do you find a more richly gifted animal? Even man has a rival in the Hymenopteran [ants and bees]. We build cities, so does he; we keep servants, so does he; we breed domestic animals …he has his milk cows, the aphids. ...To consider the animal means to ask a disquieting question: Who are we? Where do we come from? Thus: what goes on in this tiny Hymenopteran brain? Are there abilities related to ours, is there a form of thinking?" --Jean-Henri Fabre 1882

Comparing ants to humans can yield intriguing insights, as I describe in Skeptics magazine, “Apples and Oranges, Ants and Humans: The Misunderstood Art of Making Comparisons."

For example, I was invited to write a review for a leading business publication, the Journal of Organization Design, comparing the organization of ant colonies to human institutions, which was published alongside commentaries by business leaders. (We learned from each other!)

I have worked on a variety of ants around the world, but am best known for research on the Asian marauder ant, which has workers that vary in size 500 fold in service of a complex division of labor. The ants forage in swarms in the manner of some army ants, as described here. For more on marauder ants, with photos, see my entry in the Encyclopedia of Social Insects.

The years focused on writing the book Adventures Among Ants yielded ideas I still pursue. I am especially intrigued by what supercolonies—ant colonies that have expanded into the trillions—tell us about maintaining societies. For a description for the general audience, read The Scientist and a Smithsonian Magazine video by Melissa Wells of me looking at leafcutter ants.

Want to know how much ants control the world? Here’s my lecture for the conference “Human Origins and Humanity’s Future” organized by the anthropology group CARTA (the Center for Academic Research and Training in Anthropogeny), of which I am a member. And finally here's my talk for the John Templeton foundation on supercolonies of trillions in an invasive ant.

Moffett, M.W. et al. 2021. Ant colonies: Creating complex organizations with minimal brains and no leaders. Journal of Organization Design 10:55-74. PDF

Moffett, M.W. 2019 The social secret humans share with ants. Wall Street Journal, 6/10. PDF

Sorger, D.M., W. Booth, M. Lowman, M.W. Moffett 2017. Outnumbered: A new dominant ant species with genetically diverse supercolonies in Ethiopia. Insectes Sociaux 64:141-7. PDF

Moffett, M.W. 2014. Why Ants don’t Play. American Journal of Play 7:20-26. PDF

Moffett, M.W. 2012. Supercolonies of billions in an invasive ant: What is a society? Behavioral Ecology 23:925-933. PDF

Moffett, M.W. 2011. Ants & the art of war. Scientific American 305:84-9. I review the patterns of aggression in ants, and the parallels to warfare in humans. (For an online article that builds further on this topic see the Undark website.) PDF

Collaborations

I have been fortunate to work on expeditions with wonderful colleagues. An example: Here four biologists at U.C. Berkeley's Museum of Vertebrate Zoology worm into pantyhose as protection from leeches in Vietnam (from left to right: rodent expert extraordinaire Jim Patton; salamander authority Dave Wake; herpetologist-at-large Ted Papenfuss; and snake maestro Harry Greene).

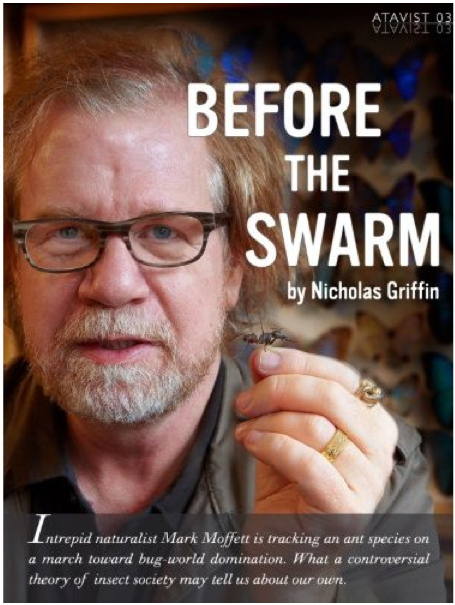

Before the Swarm

The Kindle single "Before the Swarm” (click image to open) by journalist Nicholas Griffin documented my evolving thoughts about societies before I wrote The Human Swarm.

Articles covering my scholarly work have also appeared in Harvard Magazine and The Sun.

Here is a list of my academic publications.