My exhibit at the current Venice Biennale for Architecture is accompanied by the following text:

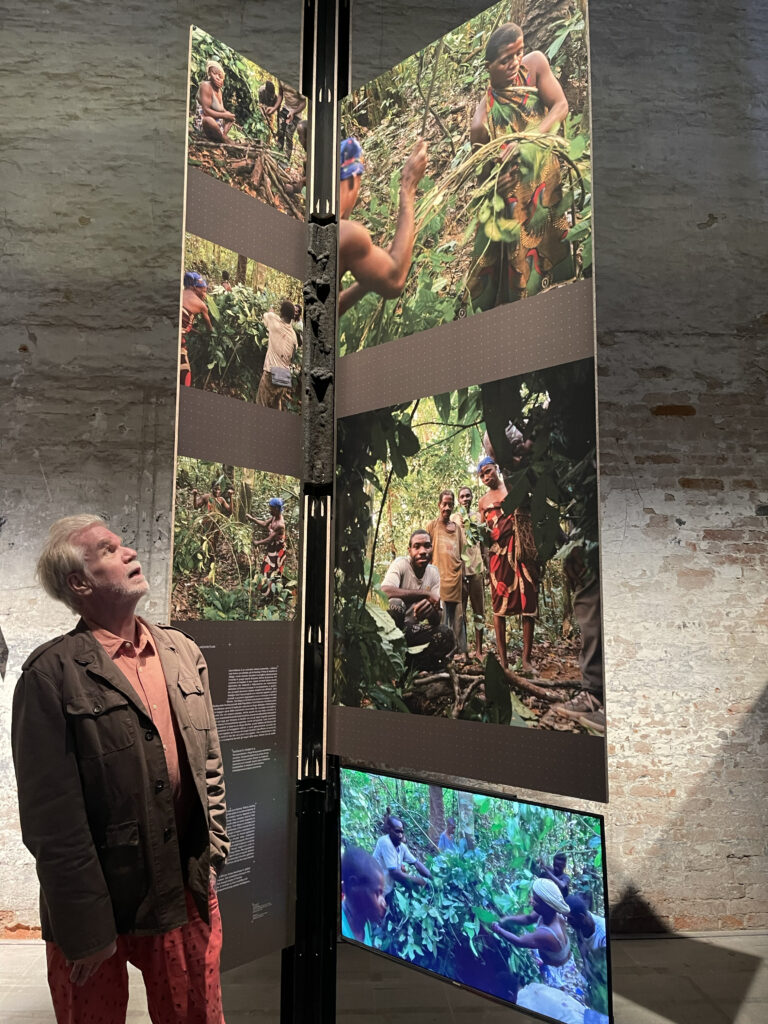

“Architecture is a human universal.” Or so archeologists have proclaimed. Before settling into villages, our hunter-gatherer ancestors crisscrossed the globe in scattered bands of a few dozen. For hundreds of thousands of years these nomads had to depend on the materials at hand to assemble makeshift dwellings wherever they camped, and so their designs needed to be simple, yet reliable. Each family would draw on plant materials or animal hides; rocks or soil could be added for reinforcement. My images and videos show Ba’Aka “pygmies” from the rainforests of the Central African Republic interweaving saplings on which they layer leafy sprigs to build a customary and, in this instance, extremely short-term retreat. Like most other constructions known for hunter-gatherers both of recent times and the distant past, this one has a circular base; sedentary communities, investing in longer lasting structures, shifted to the rectangular floor plans that are the norm today to take advantage of the ease with which angled spaces could be subdivided into functionally separate rooms. While the word “house” might not come to mind when looking at a Ba’Aka shelter, these residents of the Congo Basin, like populations of foragers elsewhere, have generally moved over the landscape in such a regular fashion as to return to familiar sites that provide a sense of home. The diversity of hunter-gatherer lifeways, encompassing a wealth of traditions like those reported here, have vanished from all but the most remote corners of the earth.